During the late stage of the project, our NFL historian, Dan Daly, vetted Chapter 22 -- which details Bill Belichick's operatic split from Bill Parcells following three seasons on the Jets -- and declared it to be perhaps the book's best section. Featuring the strangest resignation in NFL history, the chapter also revealed the story of Charlie Weis double-crossing Big Bill only days after he'd secretly pleaded for the gig that had been abandoned by Little Bill. Dan, a discriminating reader, felt that the chapter read like an episode of The Sopranos while illustrating the inherent tension between a top assistant and his boss -- two coaching greats. So I'd figured that once SI got a sneak preview, it might consider excerpting the Belichick-Parcells Split, if not perhaps the book's zaniest chapter, # 32: Falcons owner Arthur Blank sitting in Bill's dining room, trying to finalize a contract with Coach before Dolphins owner Wayne Huizenga makes a last-minute phone call scuttling the deal.

Three weeks before the book's October 28 release, Sports Illustrated sought permission to excerpt the Belichick-Parcells Split. Tammy Blake, the publisher's PR chief, delivered the exciting news to us. Space constraints required SI to trim the chapter -- always a potential pickle for any author. However, the shortened version maintained the manuscript's tone and took zero liberties. So in a no-brainer decision, Bill and I approved the licensing agreement with the magazine. The neatest aspect of the development was that SI seemed equally gung-ho about publishing the chapter. On Saturday morning, October 11, Norm Pearlstine, the chief of Time Inc., which owns SI, sent me a brief email that made my weekend: "Just read the excerpt running in SI. Great stuff." I'd gotten to know Norm a bit only because in late 2005, he and his imminent successor John Huey had approved ending a hiring freeze at the magazine, allowing me to come on board. Regardless, after reading Norm's email about the excerpt, I said to myself: Wow. The boss of bosses -- who had returned to Time Inc. in late 2013 after several years as the content chief of Bloomberg L.P. -- had read the chapter. And Norm enjoyed it enough to send me an unsolicited compliment, which I shared with Bill. The book was on its way!

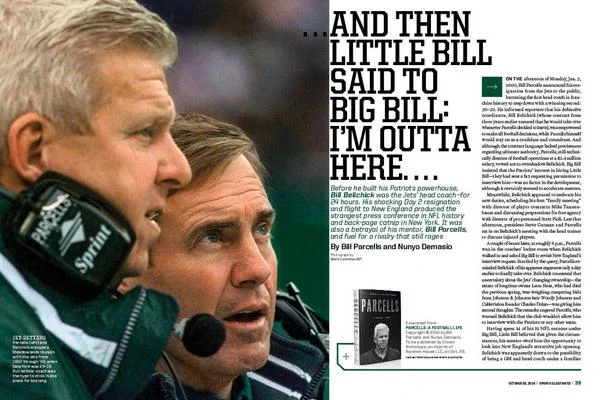

I loved SI's headline: "And Then Little Bill Said To Big Bill: I'm Outta Here..." The iconic magazine gave us five pages of expensive real estate, and placed our names on the cover of its October 16, 2014 issue. In a win-win situation, SI's article generated buzz about Parcells -- including plenty of media coverage -- ahead of its October 28 release. And the magazine piece was among the most-read articles on SI.com that week. Below this cover image is the full version of the chapter.

In a staff meeting later that morning, Bill Parcells informed his coaches of the big transition. He left the room early to allow Bill Belichick to start acting as the new Jets head coach, and Parcells’s former lieutenant stepped in with information about the upcoming Senior Bowl, and scheduled the next staff meeting.

Parcells soon gathered his players into Weeb Ewbank Hall’s audito- rium, used for team meetings and press conferences. Holding a micro- phone at the front of the room, he told the group that he no longer desired to be an NFL coach. Despite still possessing the requisite energy, Parcells lacked the commitment that he himself had always demanded from his players. He didn’t want to fool himself, or anyone else, by returning to an all-consuming job. To more eloquently convey those feelings, Parcells concluded his resignation speech by reading Dale Wimbrow’s poem “The Guy in the Glass.”

When you get what you want in your struggle for self, And the world makes you king for a day,

Then go to the mirror and look at yourself,

And see what that guy has to say.

For it isn’t your Father, or Mother, or Wife,

Whose judgement upon you must pass.

The feller whose verdict counts most in your life

Is the guy staring back from the glass.

He’s the feller to please, never mind all the rest,

For he’s with you clear up to the end,

And you’ve passed your most dangerous, difficult test

If the guy in the glass is your friend.

With four lines left, Parcells’s booming voice started cracking as his eyes welled up. But he read the poem’s final lines with power.

You can fool the whole world down the pathway of years,

And get pats on the back as you pass,

But your final reward will be heartaches and tears

If you’ve cheated the guy in the glass.

Parcells released the microphone and stepped away from the stage. In previous emotional addresses Parcells had tried to fight off tears. But this time he cried unabashedly as he headed out of the auditorium. Walking out, Parcells felt a love from his players, many of them teary-eyed, as they remained in their seats. The players glanced at each other, uncertain of what to do or say. And for a few minutes, no one spoke.

During the afternoon, Parcells announced his resignation to the public, becoming the first head coach in franchise history to step down with a winning record: 30-20. He informed reporters that Bill Belichick was em- powered to make all football decisions, while he himself would stay on as a confidant and consultant. Although the contract language lacked precise- ness regarding ultimate authority, Parcells, still technically director of foot- ball operations at a $2.4 million salary, vowed not to overshadow Belichick. Big Bill insisted that New England’s interest in Little Bill was no factor in the development, although it certainly seemed to accelerate matters.

Around the same time, Woody Johnson raised his offer for the Jets from roughly $600 million to $625 million, vaulting over the latest exor- bitant proposal by Charles Dolan. Johnson’s bid was the highest ever for a New York sports franchise. Having exchanged increasingly breathtaking offers with the Knicks season-ticket holder since early December, Dolan now needed to go up another notch. Meanwhile, Belichick seemed to embrace his new duties, scheduling his first “family meeting” with Mike Tannenbaum and discussing preparations for free agency with Scott Pioli. In the late afternoon, Gutman and Parcells sat in on Belichick’s meeting with the head trainer to discuss injured players.

A couple of hours later, at roughly 6 p.m., Parcells was in the coaches’ locker room when Belichick walked in and asked to revisit New England’s fax. Startled by the query, Parcells reminded Belichick of his eagerness on Saturday to finally take over. Belichick countered that uncertainty about the Jets ownership was giving him second thoughts. Those remarks angered Parcells, who warned Belichick that the club wouldn’t allow him to interview with the Patriots, or any other team.

Having spent fourteen of his nineteen NFL seasons under Big Bill, Little Bill believed that, given the circumstances, his mentor owed him the opportunity to look into New England’s attractive opportunity. Belichick was apparently drawn to the possibility of being a GM and head coach under a familiar owner like Kraft, as opposed to working for a neophyte owner like Charles Dolan or Woody Johnson while Parcells hovered with an unclear role. Parcells reminded Belichick about his contract, noting that Hess had paid the heir apparent a king’s ransom during the previous off-season. Parcells ended the conversation by stressing that if Belichick bailed out of his three-year, $4.2 million contract, the organization in- tended to seek compensation.

Parcells recalls, “He made a deal, and then tried to get out of it. A deal’s a deal. You want out? You’re going to pay. Simple.”

Despite the testy exchange, when Belichick departed the coaches locker room Parcells assumed that his former lieutenant had been merely exploring his options. Belichick’s behavior, however, changed dramatically the next morning, several hours ahead of a 2:30 p.m. Q&A to introduce him as Parcells’s replacement. He appeared nervous and agitated while interacting with colleagues, which was odd for an ex–head coach groomed to guide the Jets. In Tuesday’s staff meeting, Belichick couldn’t prevent his hands from shaking. He ended the caucus early, telling his coaches that he would get back to them to reschedule.

After Parcells taped a weekly TV show with Phil Simms, the erstwhile head coach returned to his office at roughly 2:15 p.m. About five minutes later, Belichick swung by to deliver a bombshell: the new head coach in- tended to use his introductory press conference to announce his resignation. Parcells was surprised, though not quite shocked given Belichick’s recent behavior. Still, the Jets chief seethed, reiterating that the club would bar Belichick from interviewing elsewhere, putting him in coaching limbo.

Minutes before his press conference Belichick passed by the offices of several colleagues to give them a heads-up. He spotted Steve Gutman standing by his doorway after the team president had caught wind of the shocker. Belichick handed Gutman a loose-leaf sheet of paper containing three handwritten sentences. The first line read, “Due to the various uncertainties surrounding my position as it relates to the team’s new owner- ship, I have decided to resign as the HC of the NYJ.” Stunned and angry, Gutman followed Belichick to the auditorium to hear more details of the surreal switcheroo. Parcells, though, remained in his corner office down the hall, working on a short list of candidates to replace Belichick.

Wearing a dark-gray suit, light-blue shirt, and navy patterned tie, Belichick took the podium. The forty-seven-year-old removed several sheets of paper from his suit’s left inside pocket. Reading a script that in- cluded the first line from his resignation letter, Belichick astonished a full house of journalists and TV cameramen. His opening statement ran for twenty-five minutes in a voice that occasionally cracked. He often ges- tured with his hands as sweat glistened from his brow.

Belichick said, “The agreement that I made was with Mr. Hess, Bill Parcells, and Mr. Gutman, and that situation has changed dramatically. And it’s going to change even further.” He noted that the franchise had been expected to find a new owner by December 15, 1999. “There are a lot of unanswered questions here,” he told reporters. “I have been concerned about it since Leon Hess died.”

To Parcells’s chagrin, Belichick revealed a slice of their private conversation from the previous day. “He told me, ‘If you feel that undecided, maybe you shouldn’t take this job.’ I took Bill’s words to heart—thought about it last night.” Belichick evaded questions about his coaching future while expressing contentment about the opportunity to spend more time with his wife, Debby, and their three children. Nonetheless, he conceded that he had hired a noted sports-labor attorney, Jeffrey Kessler, to extricate him from his contract.

After Belichick departed the auditorium, Steve Gutman took the po- dium. The team president tried to make sense of the organization’s los- ing two head coaches within twenty-four hours, a period that included perhaps the strangest resignation in sports history. Referring to Belichick, Gutman said, “We should have some feelings of sorrow and regret for him and his family. He’s obviously in some inner turmoil.”

The partnership between Belichick and Parcells had held together well during their sole season under Kraft, but the relationship had regressed during three seasons with the Jets. Despite Belichick’s substantial growth in the NFL under Parcells, and a guaranteed position as head coach, he ached to prove himself without his primary mentor and occasional tor- mentor. As Gang Green overcame a disastrous start in 1999, Parcells’s words had been as harsh as ever.

Further complicating their partnership, the Jets organization contained a so-called Cleveland mafia, employees who had worked under Belichick with the Browns. The group, which even included Parcells’s son-in-law, Scott Pioli, seemed more loyal to the heir apparent than to the incumbent football chief. After Hess’s death, members of the coterie quietly realigned themselves with Belichick, while offensive coordinator Charlie Weis also started getting closer to his future boss. The dynamic created tension between the ex-Browns contingent and most of the coaches with deep ties to Parcells, like Dan Henning. So Belichick’s resignation upended the orga- nization well beyond the head-coaching position.

A few hours after the shocker, Belichick contested his inability to interview with other NFL teams by filing a grievance with the league office. Gang Green countered by sending the NFL copies of his contract.

The next day Commissioner Paul Tagliabue faxed every club that until a final ruling, Belichick remained unavailable for employment consideration without Gang Green’s consent. The back-page headline of the New York Post mocked, “Belichicken: Jets Better Off Without Quitter.” Another headline punned, “Belichick Arnold.” Belichick recalls, “I knew I did the right thing, and I didn’t know where my career was going.”

The Jets couldn’t postpone the Senior Bowl or free agency because of their internal dysfunction, so Parcells conducted an emergency staff meeting, outlining steps the organization would be taking in the upcoming weeks. While showing zero desire to reclaim head-coaching duties, Parcells withheld his thoughts about a replacement. When the meeting ended, Charlie Weis lingered to seize a private moment. Making sure no colleagues lurked within earshot, Weis implored Parcells to pick him as the new head coach.

“I can do this job. I’m your guy.”

Parcells, though, was already targeting a colleague he had valued since the late 1960s, with whom he had worked at two colleges and three NFL teams. By lobbying zealously Weis was jeopardizing a spot on any new coach’s future staff, so Parcells firmly rebuffed the offensive coordinator he had elevated from wideouts coach in 1997, cutting the conversation short.

One week later, on January 11, Robert Wood Johnson IV won the right to purchase the Jets for $635 million, the third-highest price ever paid for a professional sports team. Based on Leon Hess’s will, the transaction meant $5.1 million for Steve Gutman beyond his salary. Known for donating money to autoimmune-disease research and Republican campaigns, Johnson ran a private investment firm on Fifth Avenue named after him. Much of the fifty-two-year-old’s wealth, though, came from Johnson & Johnson stock.

His football jones stretched back several decades. While attending the University of Arizona, Johnson co-published Touchdown, a guide for Monday Night Football, which dissolved after three issues. But he was known more for his carousing, once reportedly falling eighteen feet off a darkened bridge in Tempe and breaking his back after pulling his car over to urinate. During his late twenties, Johnson had coveted the Tampa Bay Buccaneers as an expansion team. Now he had landed the Jets after Dolan declined to raise his latest bid of $612 million. Only hours after the cable TV magnate ceded, Johnson telephoned Parcells to introduce himself.

Taking the call with Mike Tannenbaum in the room, Parcells remarked, “Congratulations. being in pro football is not for the well-adjusted.”

Johnson replied, “That’s good, because I’m not well-adjusted.”

Parcells shared Johnson’s riposte with Tannenbaum. At the least their new owner had a good sense of humor. Or was he being serious?

Johnson and his football chief soon met for a brief discussion focusing on Belichick. The owner agreed with Parcells that Gang Green shouldn’t free Belichick without obtaining at least a first-round pick. Their follow- up meeting was wide-ranging, with Johnson sharing his vision for the franchise. He implored Parcells to return to the sidelines, but the director of football operations declined. Johnson expressed an inclination to con- duct a league-wide search for a top candidate, but Parcells insisted on continuity for a team only one season removed from an AFC Championship appearance. Parcells suggested promoting a talented disciplinarian with deep ties to him: linebacker coach Al Groh. The tough-nosed assistant’s only experience as a head coach had come at Wake Forest from 1981 to 1986, and based on his 26–40 record at the ACC school, Groh seemed like an improbable choice for head coach. Nonetheless, Johnson deferred to the franchise’s mastermind.

Belichick’s grievance hearing came Thursday, January 13, at the Times Square headquarters of Skadden, Arps, the NFL’s counsel. Charlie Weis and Bill Parcells were required to appear at a thirty-eighth floor office after Jeffrey Kessler, Belichick’s attorney, named them as witnesses along with his client. The Jets, represented by Steve Gutman and the club’s counsel, didn’t designate any witnesses. With Paul Tagliabue present for the 9:45 a.m. start, the opposing groups sat across from each other at a conference table. Each side made fifteen-minute opening statements. Then Kessler called Parcells as the first witness for a Q&A that lasted forty-five minutes.

Charlie Weis started testifying next, and his statements jolted Parcells even more than Belichick’s resignation. During four minutes of testimony Weis supported Kessler’s main argument that Parcells had no intention of ceding true authority to Belichick. The offensive coordinator claimed he had overheard Parcells telling Gutman that Belichick wouldn’t quite gain the power he was contractually due. Parcells had known that Weis would testify, but never imagined him speaking so forcefully on Belichick’s behalf. Dan Henning recalls the situation: “Bill [Parcells] decides to go with Al; Belichick can’t coach for a year. Charlie [Weis] realizes that he has nothing. So that’s when he goes and thinks that he can get Belichick out of trouble by putting Bill [Parcells] in trouble.”

Weis’s NFL coaching career had started in 1990 when Parcells hired the Jersey high school coach to an entry-level position. Impressed by Weis’s offensive acuity over the years, Parcells had promoted him multiple times with the Patriots and Jets. Parcells could only conclude that now Weis was ingratiating himself with Belichick, hoping for a position in New England.

Kessler called his client as the third and final witness before a Jets lawyer cross-examined Belichick. The grievance hearing ended after roughly seven hours, and a ruling was expected within a week. Weis returned to his office the next day, but that move proved foolhardy when Parcells spotted him in the hallway. Incensed, the Jets chief immediately banned his offensive coordinator from the premises. “Charlie, you need to get your shit and leave the building.” Watched closely by Jets employees, Weis took only a few minutes to gather some items before scuttling out of the build- ing. Moments after he exited, the team packed up the rest of his belong- ings and shipped them to his home.

Parcells says, “I’ve told many coaches that friendship and loyalty is going to be more important than ambition. Some guys don’t realize that until after they’re done. I don’t bear any animosity toward Charlie. I can say that with a straight face because I know what he is. When somebody shows me what he is, I usually believe it. His actions back then don’t bother me anymore.”

On January 21, Tagliabue ruled for the Jets, reasoning that Belichick had breached his contract by quitting. The league prohibited him from coaching in 2000 without the Jets’ consent or compensation. Tagliabue’s explanation echoed the one in 1997 that had prevented Parcells from joining Gang Green without New England’s permission.

Three days after Belichick’s setback, the Jets named Al Groh as their new head coach with a four-year contract averaging $800,000. The fifty- five-year-old promoted Dan Henning to offensive coordinator, and hired Mike Nolan as defensive coordinator. Other notable additions included tight-ends coach Ken Whisenhunt and secondary coach Todd Bowles. Groh picked his son, Mike, as a quality-control assistant on offense. On the day of Groh’s official elevation, Belichick made a last-gasp attempt to overcome Tagliabue’s ruling by filing an antitrust lawsuit in federal court against the Jets and the NFL.

by gaining 1,464 rushing yards to help his injury-ravaged team avoid a losing season, Curtis Martin had been voted Jets MVP. He planned to give the trophy to the person who most shaped him as a football player and person: Bill Parcells. On January 24, Boy Wonder found out exactly when the Jets chief was meeting with the new coaching staff. That afternoon, Martin slipped into Parcells’s corner office while carrying his trophy and a one-paragraph letter with neat penmanship: seven sentences in blue, felt-tip ink summed up his feelings about Parcells. Boy Wonder placed the items on Parcells’s desk before slipping out undetected.

After the meeting Parcells walked into his office and immediately noticed the tall, gleaming trophy. “What the hell is this?” Parcells said aloud. He walked closer to inspect it, and spotted a white sheet of paper next to the trophy. As Parcells sat down to read it he received a phone call from his youngest daughter. Picking up the receiver to greet Jill, Parcells remained mesmerized by Martin’s note, quickly reading it through to the end. A few moments later, Jill heard her father quietly sobbing.

“Dad? Are you okay? What’s wrong?”

The letter, dated January 24, 2000, in the bottom left corner, read:

Coach,

This award is the best and most

gratifying I've ever received.

It means more than the pro bowls,

the rushing title and the team records.

You've given me and football some of your

best years -- and as a little token

of my appreciation I give you my best.

I thank you from the bottom of my heart

for all that you are and all that you have

done for me! Your'e like a father to me.

Love ya!

Boy Wonder

Late that night, Parcells headed home with the trophy and letter. He would laminate the note, and keep both in a glass case among his most prized possessions. The gift provided a much-needed salves amid the upheaval of Bill Belichick's departure.

On Tuesday, January 25, a federal judge denied Belichick’s request for a temporary restraining order, ruling that his Jets contract was valid. Accepting the futility of his situation, Belichick withdrew his antitrust lawsuit against Gang Green and the NFL. The development enhanced the team’s leverage, prompting Parcells to consult Woody Johnson about bro- kering a deal with Kraft on compensation for Belichick’s services.

Parcells found the notion distasteful given his acrimonious divorce from Kraft; the two essentially hadn’t spoken since the week following the 1997 Super Bowl. Nonetheless, Parcells knew a deal would benefit both sides, and he believed that as a savvy businessman, Kraft would embrace the opportunity to bolster his franchise. Furthermore, talks would signal a truce in what Parcells termed the “border war” between New England and New York.

So that same day Parcells telephoned Kraft’s office and identified himself to the owner’s secretary. Surprised by the call after years of smoldering silence, Kraft gave the go-ahead to pipe him in. When the owner picked up, Parcells said, “Hello, Bob, this is Darth Vader.”

Kraft laughed, easing some of the tension.

When his nemesis broached the possibility of a resolution involving Belichick, the Patriots overlord was immediately receptive. Before going farther, however, Parcells expressed regret for some of his actions in New England. Kraft responded by conceding that his inexperience as an NFL owner had exacerbated the situation.

Getting down to business, Parcells informed Kraft that the Jets would allow Belichick to coach New England in exchange for compensation via draft picks. Kraft offered a third-round pick in 2000 and a fourth-rounder in 2001. Parcells quickly countered that a deal required at least a first- round selection in 2000. The conciliatory conversation ended after forty minutes, with plans for further talks in the morning.

In their next session, Kraft increased his offer to a second-round pick in 2000 and a third-rounder in 2001, but Parcells insisted on a first-round se- lection. The two men hung up politely without a deal. Later that afternoon, Kraft interviewed Jaguars defensive coordinator Dom Capers for more than four hours. Parcells expected New England to hire Tom Coughlin’s lieu- tenant as their new head coach, leaving Belichick in limbo and Gang Green without compensation for his departure. However, as Parcells headed to bed around 11 p.m., Kraft surprised him with a phone call.

“I’m going to make a decision here that I don’t want to make, because I want this guy as my head coach.”

Parcells replied, “We can work this out. Let’s do it.”

Kraft agreed to relinquish his upcoming first-round pick if the teams exchanged a couple of lower-round selections in future years. Sealing the deal, the Jets chief made an unusual suggestion: that they place a two-day window on Belichick’s contract negotiations with New England in order to prevent him from holding either organization hostage. Kraft loved the idea.

Knowing about the earlier stalemate, Belichick was flabbergasted when Parcells called him at 7 a.m. to reveal the agreement he’d reached with Bob Kraft, contingent on Belichick’s signing a contract with the Patriots in less than forty-eight hours. Parcells also granted Belichick permission to hire two Jets staffers with whom he shared links to the Cleveland Browns: Eric Mangini and Scott Pioli. After all but firing Weis, Parcells gladly allowed the banished coach to join Belichick, too. Jets PR assistant Berj Najarian, who had grown close to Belichick at Weeb Ewbank Hall by perennially staying there late, was also on his wish list, to which Parcells also gave his approval.

Around 10 a.m., Kraft called Bill Belichick to confirm the arrangement and start negotiating a contract. After hanging up Belichick telephoned Mangini, Pioli and Najarian about heading to New England. Within a few hours Belichick drove the three men to Foxboro Stadium, where he reached a handshake agreement with Kraft on a contract to be finalized later.

At 6 p.m. that same day the Patriots introduced Bill Belichick as their new head coach, with more power over personnel decisions than Kraft, as a neophyte owner, had permitted Parcells. Belichick took the opportunity to reiterate that he had quit the Jets mainly because of the franchise’s fluid ownership at the time, and Parcells’s unclear role. Addressing the issue of escaping his mentor’s shadow, Belichick noted that Parcells had also left a vast one in New England.

Parcells says of Belichick, “At the end of the day, he didn’t want to be the Jets head coach. Then he expected me as the general manager of the organization to just say, ‘Okay, I’ll get somebody else.’ Well, eventually, I did that. But I got compensation because I knew what Kraft was doing before the season ended. I didn’t begrudge Bill getting another job some- where else. In fact, I’m probably the one that got it for him.”

Reflecting on his decision to quit the Jets, Bill Belichick says, “At that point in time, in that situation, I did what I felt I needed to do, and I don’t have any regrets about that. Certainly a lot of things could have been handled differently.”

beyond losing Belichick, Gang Green faced a dilemma involving one of its top players: Keyshawn Johnson was expected to hold out during training camp if the Jets failed to upgrade his rookie contract, which had two years remaining on it. The six-year, $15.4 million deal, which had been reached after a holdout lasting almost a month, included the largest bonus for a rookie receiver: $6.5 million. However, after two consecutive Pro Bowl seasons, the loquacious wideout felt underpaid by the $2.4 million due in 2000, when lesser receivers were earning substantially bigger salaries.

During the previous off-season Parcells had tried to restructure Johnson’s deal in a way that would both avoid the salary-cap consequences of an extension and keep the wideout long-term. The NFL, however, ruled that the unusual proposal was in violation of cap rules. Gang Green sus- pected that the decision involved fallout from Curtis Martin’s controversial contract. To further complicate matters, Jets policy prohibited renegotiat- ing deals with at least two years left on them, and Parcells disliked the scorched-earth tactics of Johnson’s Los Angeles–based agent, Jerome Stanley, who demanded a new deal that included a $12 million bonus.

Parcells met with Al Groh, Dick Haley, and Mike Tannenbaum to weigh the team’s options: force Johnson to stay, despite the disruption of another holdout; trade him to the highest bidder; or grant him a lucrative extension, setting a precedent that would hamper Gang Green’s efforts to retain key players. Eager to start his tenure without distractions, Al Groh favored jettisoning the wideout, so Parcells consulted Keyshawn John- son about reaching a mutually beneficial decision. In Parcells’s office they spoke about the possibility of finding a team willing to meet Johnson’s contractual demands.

Johnson noticed a thick binder on Parcells’s desk used for organizing his personal and financial life. After the football talk, he asked Parcells if he could take a closer look. The Jets chief obliged, and explained its pur- pose as Johnson leafed through the binder, which included a wide range of sections: property tax estimates, book deals, endorsement contracts, horse racing, income statements, correspondence, donations, investments. When Parcells suggested that Johnson get something similar to help orga- nize his life, the wideout latched on to the idea, and responded with deep appreciation. The heartfelt exchange put an unusual coda on their strategy session for navigating the cutthroat business of football.

“Keyshawn can be full of shit, but he’s a good listener,” Parcells says. “When you’re talking about something serious, he’s paying attention.”

On April 12, the Jets made one of the most stunning trades in fran- chise history, sending their star wideout to Tampa Bay, an offensively challenged team with Super Bowl expectations based on a dominant defense, for two first-round picks in the upcoming draft. The Buccaneers agreed to extend Johnson’s contract by six years and $52 million, including a team-record $13 million bonus that made him the highest-paid wideout of all time. Despite losing a major offensive weapon, Gang Green ended up with an NFL record four first-round choices, including the one ac- quired for Belichick’s services.

The Jets used those selections to draft defensive lineman Shaun Ellis (twelfth overall) of Tennessee, defensive end John Abraham (thirteenth) of South Carolina, quarterback Chad Pennington (eighteenth) of Mar- shall, and tight end Anthony Becht (twenty-seventh) of West Virginia. Gang Green’s next selection didn’t come until the third round, when the team was considering drafting Florida State wideout Laveranues Coles, whose stock had dropped because of a rap sheet. As a college senior, Coles was arrested with fellow wideout Peter Warrick for shoplifting at Dil- lard’s, prompting the Seminoles to remove him from the team. A prior incident in 1998 had brought Coles a simple battery charge, triggering a one-game suspension. Nonetheless, Steve Yarnell advocated for Coles because the security chief’s background check, which included a visit to Tallahassee, found extenuating circumstances in the wideout’s troubles. With Coles still available for Gang Green’s seventy-eighth overall choice, Parcells tersely asked Yarnell in the draft room whether the wideout would end up embarrassing the organization.

Yarnell pushed back. “I’m telling you, this is our guy!” The security chief’s conviction helped sway Gang Green to pick Coles. Its 2000 draft class would bolster the roster for years, and the talented five-eleven, 200-pounder performed well while behaving like a model citizen.

Despite the tumultuous off-season, Al Groh’s Jets captured their first four games with Vinny Testaverde back at quarterback. The first such streak in franchise history included two stirring comebacks: 20–19 at home versus Bill Belichick’s Patriots on two final-period touchdowns by Wayne Chre- bet, and 21–17 on the road against Tony Dungy’s Buccaneers, after Boy Wonder threw the game winner to Chrebet while Keyshawn Johnson fin- ished with just one catch for a yard.

Instead of attending games in his new role, Bill Parcells drove from his home in Seagirt, New Jersey, to Weeb Ewbank Hall, where he watched Gang Green on TV. The decision stemmed from Parcells’s desire to keep from overshadowing his rookie NFL head coach, especially on game days. At most Parcells might telephone Mike Tannenbaum to chat before a contest while navigating the Jersey Turnpike past Giants Stadium, heading for Long Island. Mr. T’s game-day responsibilities placed him in the Jets coaches’ booth.

Less than two hours before Gang Green hosted the Dolphins on Monday Night Football, Parcells telephoned from the highway. “All right Mr. T, what’s going on?”

Tannenbaum replied, “Nothing much; usual pregame stuff. Are you coming?”

“Hmmm. No.”

With the Jets playing Miami for first place in the AFC East, Parcells’s superstitious nature reinforced his decision to stay on the periphery. Gang Green improved to 6-1 after the “Monday Night Miracle,” the greatest comeback in franchise history and on the prime-time series. Down 30–7 in the fourth quarter, Gang Green tied the game with 1:20 left on Tes- taverde’s 3-yard pass to left tackle Jumbo Elliott who made a juggling catch while falling in the end zone. The improbable reception, the only touchdown of Elliott’s career and Testaverde’s fifth of the night, led to overtime. The Jets triumphed, 40–37, in a stadium that ended up being half empty mainly due to the departure of fans who had given up hope.

Groh’s team, however, failed to sustain the magic, subsequently losing three straight. The slide tortured Parcells, given his vow not to microman- age. Although the Jets chief had observed some reasons for Gang Green’s troubles, he felt that steering Groh would undermine him. However, Parcells was spending more time than ever discussing how to build a team with Mike Tannenbaum, who ended up receiving his boss’s private complaints about Groh’s decisions.

Perplexed by the information, Tannenbaum asked, “Bill, why don’t you tell Al instead of me? He’s the one who needs to make the changes you’re talking about.”

Parcells replied, “Mr. T, I just can’t tell Al. He has to do things in his own way.”

Tannenbaum says now, “Bill never really found his stride being the GM because he didn’t want to overstep his bounds.”

The director of football operations still found ways to motivate his favorite Jet, Boy Wonder. During one conversation after the sixth-year veteran described his rigorous training regimen that dated back to his rookie season, Parcells replied, “Son, don’t confuse routine with commitment, because you’ve got to do more the older you get, or you’re losing ground. A lot of people fall into a routine in their life’s work, and as time goes on they eventually confuse that with being committed to their job. The only thing they’re committed to is the routine.”

Martin suddenly realized that his workouts had fallen into a rut. Despite a reputation for being Gang Green’s hardest worker, Boy Wonder decided to revamp his routine. He recalls of Parcells’s advice, “That sparked a new flame, a higher flame.”

A three-game winning streak boosted Gang Green to 9-4, position- ing the club to make the playoffs with just one more victory. Nevertheless, Groh’s team collapsed again, losing three straight down the stretch.

On December 30, only one week after the season finale, Al Groh abruptly quit the Jets to accept his dream job: head coach at his alma mater, the University of Virginia, where his son Mike had starred as a quarterback in the mid-1990s. Al Groh, who had been an assistant coach at the school in the early 1970s, signed a seven-year contract worth more than $5 million in a deal that provided more long-term security than he had with the Jets. Reminiscent of Ray Perkins bolting the Giants for Ala- bama, Groh replaced George Welsh, sixty-seven, who had retired after nineteen seasons at Virginia.

The third Jets head coach to bail in a calendar year guaranteed that the franchise would experience another disruptive off-season, and only ten days later, on January 9, an even more powerful tremor shook the team. Bill Parcells announced his retirement from the NFL, citing reasons similar to those he’d given when he had quit as head coach, and admitting that he had experienced difficulty transitioning to his new role. As a replace- ment Parcells recommended that Woody Johnson decide among three of Parcells’s former Giants scouts: personnel executives Terry Bradway of the Chiefs, Jerry Angelo of the Bucs, and Rick Donohue of the Giants. Inter- viewing them only two days after Parcells’s resignation, Woody Johnson chose Bradway, a Giants scout from 1986 to 1992. The owner kept Mike Tannenbaum on, positioning the contract negotiator to be next in line to run the team.

On Parcells’s final day at Weeb Ewbank Hall, he secretly placed a bottle of Grey Goose on Mr. T’s desk with a note. “At some point, you’re going to need this.”